After visiting the wounded from the previous days, Albemarle and his men marched back to Pretoria where they were provided with fresh clothes. That day the Earl also caught a glimpse of Baden-Powell, the future founder of the Scouts, who had rode from Mafeking. After leaving Pretoria, marching to Irene and then to the mining town of De Springs, Albemarle regretfully was forced to leave 122 exhausted men behind before marching again. ‘They are really trying us too high. Many of our men are completely done up and utterly collapsed’, he reported sadly, ‘They have toiled on until they could do so no longer, and some of the men had tears in their eyes on being left behind the Battalion’. By the time the battalion reached Heidelberg, Albemarle solemnly reported a dramatic drop in the amount of men accompanying him, ‘The strength of the Battalion is now 604 men and 22 officers. When we left London, it was 1,048 men and about 30 officers’.

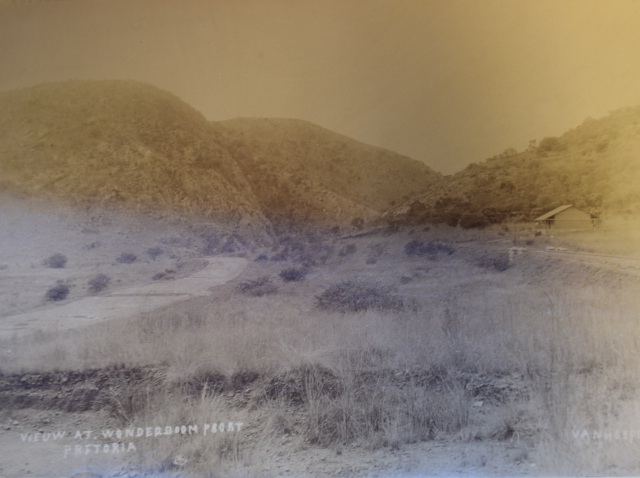

Near Pretoria. NRO ACC Albermarle 2/6/69

As the men marched on, signs of what would define the agonising second part of the Boer War would come into play. ‘We burnt two farms on the way, one of which was a model one, belonging to a Heidelberg potentate, who was out on commando’. The practise of burning Boer farms became all too common in the latter stages of the Boer War and was known as ‘scorched earth policy’. This tactic had previously been used in the American Civil War to great effect but not to the extremes that the British army would resort to which included sending the inhabitants to what are regarded as the first concentration camps. Although they had a different purpose to those in Nazi Germany, the death toll was frighteningly high and news of such atrocities caused other nations to see the British as barbarians.

Like what became of many British horses in the Boer War Albemarle commented that his steeds were ‘little more than skeletons now’ yet was happy that his remaining men were better fed and that their health was ‘pretty good’. For three weeks the men were entrenched at Heilbron where the men were involved with garrison work, anticipating any Boer attack that may arise. During this time officers and men would often indulge in cricket or football whenever they could have a break from their duties. Suddenly however, the garrison was forced to leave Heilbron. During the evacuation the enemy watched the British from the hills. To avoid bloodshed they took Boer hostages alongside them, warning the enemy that if they they were shot at, the hostages would also be shot, ‘They were all mighty frightened’ commented Albemarle. Fortunately for the British and their scared prisoners, they were met with no disturbance from the enemy.

Upon arriving in Friedrichstad an unusual event occurred in which a Boer rode towards Albermarle’s men with a white flag, uttering the words ‘surrender’. At first the earl was flattered for he thought the enemy was offering their submission before realising that it was ‘we who were expected to surrender and not the Boers’. Quickly the man was blindfolded and confined under a guard. Before long the battalion alongside the Yeomanry came into contact with the man’s comrades. They were driven back by the British guns but not before two men were killed while attending to a wounded yeoman, one of which being a stretcher bearer. The British then burnt around ‘eight or nine’ farms in revenge for the ‘murder’ of an engineer and two Kaffirs who were mending the way close to the village of Buffelsvlei.

Albemarle and his men were greeted in the capital but not before tragedy struck when Private Fenton passed away in the presence of his parents, most likely from sickness and exhaustion. Albemarle solemnly remarked it was ‘doubly sad at a moment when his comrades were about to receive, at the hands of the citizens of London, their reward, and approval for their labours in a long and honourable campaign’. The scene that met Albemarle and his men on the streets of London was a stirring one and soon they were embraced by family and friends. The earl and his battalion had done their duty well in the eventful (and controversial) South African Campaign.

Portrait of Albermarle on horse. NRO MC 2615/2, 989×6

Although Albemarle was not perfect as a leader or a person, it is clear he displayed great sympathy towards his men and they appreciated that in return. His diary is evidence that he had a very strong bond with his men and he deserves to be credited in history for his amount of compassion towards the more dispossessed members of military society.

Compiled by Rebecca Hanley, NRO Research Blogger.