October is Black History Month, and the next two blog posts will celebrate and explore the contribution and experiences of black people in both Norfolk and across the world.

There were more black people in Norwich in the 18th and 19th centuries than is generally supposed. Some were connected with the campaign against slavery – Norwich was one of the places where the anti-slavery movement was strongest – others are known of by pure chance. Three anti-slavery black campaigners with Norwich connections are James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, Olaudah Equiano and Ignatius Sancho.

Gronniosaw (1710-1773) worked for some years in the 1760s as a weaver in the city under the name of James Albert. His origins are explained in his autobiography:

‘I was born in the city of Baurnou, my mother was the eldest daughter of the reigning King there. I was the youngest of six children, and particularly loved by my mother, and my grand-father almost doated on me.’

Sold into slavery from his native Nigeria, Gronniosaw was granted his freedom in 1748 and soon after entered the British Navy. He married a white weaver, a match disliked by his friends not for racial reasons but for class considerations according to Gronniosaw, ‘because the person [he] had fixed on was poor’. In later life he lived in the West Midlands, and his story was put together and published by:

‘a young Lady of the town of Leominster, for her own private satisfaction, and without any intention, at first, that it should be made public. But has now been prevailed on to commit it to the press, both with a view to serve Albert and his distressed family, who have the sole profits arising from the sale of it; and likewise, as it is apprehended, this little history contains matter well worthy of the notice and attention of every Christian reader’.

Ignatius Sancho (1729-1780) was actually born at sea during a journey in the Middle Passage – which neither of his parents survived. He was brought up in Greenwich where he eventually found refuge with the Duke and Duchess of Montague. Sancho wrote music and entertained within literary circles, and his letters, published posthumously, were widely read in English abolitionist circles. Many of them were to William Stevenson, the Norwich newspaper proprietor, and a dedicated abolitionist. One of the letters (which were published in 1782) contains a condemnation of the slave trade then practiced by the British and most European countries. To John Wingrave, (a London bookseller);

‘I am sorry to observe that the practice of your country (which as a resident I love, and for its freedom, and for the many blessings I enjoy in it, shall every have my warmest wishes, prayers, and blessings); I say it is with reluctance, that I must observe your country’s conduct has been uniformly wicked in the East – West-Indies and even on the coast of Guinea. The grand object of English navigators, indeed of all Christian navigators, is money, money, money’.

Olaudah Equiano, (c.1745-1797), probably born in Benin, was also captured by slavers, and taken across the Atlantic. Clearly an exceptional man, he impressed his various owners and was eventually freed. His autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the life of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa the African was first published in London in 1789 (Vassa was a name assigned to him by one of his owners during his slavery). It was the first book to give a description of the horrors of the ‘Middle Passage’, the journey across the Atlantic on board a slave ship. It was taken up by anti-slavery campaigners and nine editions were published over the next five years, including one in Norwich paid for by his supporters, whose names are given in the front of the book.

The work of men like these, and their supporters in Norwich and elsewhere, led to the abolition of the slave trade by Britain in 1807. After this date, British ships patrolled the Atlantic, capturing ships of other countries that contained slaves and setting them free. The freed slaves usually went to Sierra Leone to start a new life. A small number, too young to fend for themselves, were brought back to Britain, a special form of refugee: slave children who had been taken from their parents in Africa to be shipped across the Atlantic Ocean.

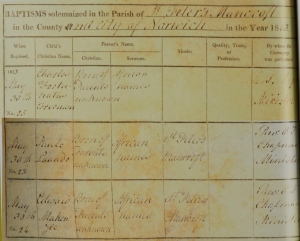

Three such boys were baptised in the font at St Peter Mancroft church on 30 May 1813. They were given the names of Paulo Loando, Edward Mackenzie, and Charles Fortunatus Freeman. We do not know what their African names had been, and we do not know what happened to them in later life. They emerge from the anonymity of the past for just this one brief moment in this Norwich church almost 200 years ago.

Three such boys were baptised in the font at St Peter Mancroft church on 30 May 1813. They were given the names of Paulo Loando, Edward Mackenzie, and Charles Fortunatus Freeman. We do not know what their African names had been, and we do not know what happened to them in later life. They emerge from the anonymity of the past for just this one brief moment in this Norwich church almost 200 years ago.

To see what Black History Month events are taking place in Norfolk, click here.

Pingback: Black History Month: Part 2 | Norfolk Record Office

Thank you for these useful insights. You mention, “There were more black people in Norwich in the 18th and 19th centuries than is generally supposed.” Do you have any ideas of the numbers and/or names?

LikeLike

Hi Jim,

I’m not sure that we have any definite numbers. This would make a great project for someone in the future.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Norfolk Notes and commented:

A good introduction to three anti-slavery black campaigners with Norwich connections are James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, Olaudah Equiano and Ignatius Sancho.

LikeLike

Pingback: The HMS Amelia and a History of Slavery – Time and Tide Museum

Good to know – my ancestor came from Norfolk and was from black descent and the gene is so strong that I still have African hair in the present day as did my father , grandfather and great grandmother ( and my great grandmothers auntie ). She married into the Suffolk family of Tills . Still trying to trace back from her marriage as I would love to know more about her and her parents who would probably be the first generation that were freed from slavery . Would love to know their story .

LikeLike

I do hope you are successful in your research…I live in Norfolk, but I am sure there will be historians in Suffolk who would be willing to assist in your important quest.

LikeLike

I recently came across entries in the Stockton, Norfolk parish accounts of the 1720s relating to a Robert Herrod receiving payments from the parish for “ye Black boys”. Does anyone know if this was a slang term, or if black youngsters would literally have been the subject of these payments?

LikeLike

Hi Paul, that’s an interesting question. I don’t know the answer but there was a Black Boy pub on the main road in Stockton. Have you got a reference for the accounts? I might be able to have a look at them if so.

LikeLike

Hi

Thank you for your response.

Here are two of the URLs from the FamilySearch website, although there are other references in the pages covering the 1720s:

https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-DTZQ-H4T

https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-DTZQ-3QP?i=298

I have only just noticed the latter reference and this does appear to suggest the reference might have been to a public house, rather than my original idea of servants, being provided by Robert Herrod to give some sort of assistance!

Living in one of the most multicultural areas of the country, the subject of early examples of black people living in England in of interest to me, but Robert does appear to be an ancestor of mine (or at least related in some way) and I was intrigued that he might have been “responsible” in some way for some black males. Probably not, though! (“For the Black Boys” might be referring to the hire of rooms there, of course.)

Regards – Paul

LikeLike

Hi Paul, thank you for those links. From the pages of accounts that you link above, and others around the time, I believe the references to be to a pub rather than people. These pages of accounts have expenditure by the parish/churchwarden on the left hand side, e.g. April 1729 Spent at ye Black boy at Easter meeting, and the right hand side are the rates being paid based on the value of the land/property, eg Robert Herrod for ye Black boys. These would all make sense in the context of a place/pub. I hope this helps.

LikeLike

Thank you so much in ending my speculation over this. I should have read the entries more carefully, and perhaps discovered this page, via Google, earlier:

https://norfolkpubs.co.uk/norfolks/stockton/stockton.htm

Interesting there was still a Robert Harrod as licensee over 150 years later (my ancestors being recorded as Herod, Harwood and Harrod (etc.) over the years.

LikeLike